WORK'S CHRONOLOGY ...edit by Paolo Rizzi

"THE SEARCH FOR THE INNER CONDITION OF MAN" edit by Erich Steingräber - 2000

Let us look at Meneghetti’s rough and hard road over these last fifty years. At the time of Fagocitanti, [1] before it, and even after, up to the beginning of his Radiografie (X-Rays) cycle [2], the very urgency of his expression was enough to stop any wide-range scrutiny from the critics; Not only this, the artist’s very restlessness, his flight from any handy aesthetic or cultural tendentiousness, his works’ continual resort to even the most convulsive for experimentation and, from 1982 on, an opening to the most varied of media, photography [3], films [4], music [5]nd theater [6], , could only serve to paralyse any historical labels. But it is for these very reasons, and only today, do we realise it, that Meneghetti is one of the clearest-cut key figures for any interpretative orientation of those stormy years from the sixties to the eighties.

The Phagocited man is a slave of the drugs, of the money [7], of the sex [8], of the power [9], of the defects [10] in general. He represent it with every instrument and when the painting is not enough he passed to the dummies [11], to the cinema, to the music, ecc. An adventurous life, then, full of ideas of genius, and it is well worth an ordered and chronological study, on the trace of these reproductions, few when you think of the myriad of experiments and the amount of research done with all manner of media and styles. Meneghetti surprises even himself: each painting is an Identikit; it reflects his nervous tics, his obsessive manias, what triggers him off, his psychoses, his frenzies.

It is not that one has to pause over some of his cycles where indeed the pictorial quality is amazing as it is for example in the portrayal of the ghostly women [12] ,of his Pornografie [13], the very Insani photos [14]and some of this photographic emulsion works (where a colour print is worked on to bring out the fantastiC]. On the contrary, there are times when Meneghetti seems to be revelling in beautiful painting, ineffable refinements come out, passages that are so subtle as to become fugitive [15]. What does count, and from a distance that by now is historical, is that his autonomy of hand is everywhere. Meneghetti certainly changes themes even, as has been pointed out. going beyond painting for his media, but his work is still recognisable, his hand is unmistakeable. There is no question of transformations, side-stepping or semantic sophistries

Then there is another feature that stays Meneghetti’s over all these over fifty years of activity, and that is his kind of sensitivity It is always subtended, neurotic, excited and you are aware of it everywhere: from the start, the painting is an «X-Ray» [16] to the point that the strokes, even when clear-cut as in the Fagocitazioni [17], and often two-dimensional, still keep something of the transparent, a sort of cartilage membrane, a fine, fragile overlay of skin that lets one see through to bone and muscle, a thin sheet of paper that reveals a sense of degeneration, nascent dissolution. In this way, his painting is always symbolic - not symbolist - in its lay out: it represents what is underneath, beyond, and makes us see beyond even before we actually see. Clearly, this capacity is born of a particular predisposition within the artist himself, but it also feeds on a technical mastery capable of guiding even the most disparate fragments back into unity, not to mention those elements of expression that could contradict each other, such as painting and photography. Cunning chromatic veiling, a magma quality in the strokes, dissolutions and blurred [18]; edges, a material swallowing-up that is at the very limits of atmospherically suspended dust as in certain of his works of half-way through the seventies - vibrations on magnetic tape, almost like writings in a trance [19], marks that become Leonardo-like, reflecting «monsters», edges that lose their definition and rediscover it. Here, it must be said, we are in the vein of painting qua painting [20]; and at a point when that was being denied. Paradoxically enough Meneghetti stays a painter even when he emerges from painting as such.

From the very start, it has been a tactile prehensile quality and visual curiosity that have carried Renato Meneghetti’s work ahead. He was born in Bassano in 1947 and when he was just seven, he recounts, « I was a child and my mother did not like me getting the floor dirty with paint, so there came a time when she refused to give me any more money to buy them. So what did I do? I gathered leaves, dry ones and green ones, I ground up a brick and collected earth from here and there. These I mixed up with olive oil (we had a shop) and I ripped up an old sheet and nailed it to the four sides of a box, to paint on. In other words, despite parental opposition, I went on painting ».

This could well pass for a sweet little story were it not for the fact that it is also indicative of a seven year-old that not only had a bent for painting, but also for its materials, he wanted the feel of them under his fingers.

What, in a sense, he also wanted to do was to see «beyond». Let me quote another episode of Meneghetti’s if only to show his propensity for optical dynamics. « I was a curious child and fascinated by the film world: how did they do it? I was eight at the time and, if I can say this, I «invented» a kind of film machine. I looked out some photo negatives and glued them together into a strip. Then I took a shoe-box and cut a hole in it and in this I put a cardboard tube. Then I stole our home help’s glasses and with a light-bulb inside the box, moving the strip up and down and focussing with the glasses, it seemed to me that I had reinvented moving pictures. ”

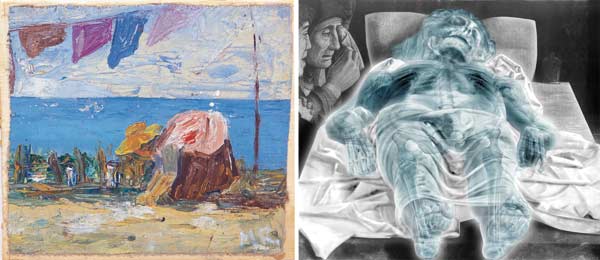

These two episodes are also eloquent of the «mania» that was inside this artist as a young child. None of his early and undoubtedly rudimentary output remains. But the incunabula are there, hanging in one part of the studio. These are several proper paintings done in 1960, when he was seven: “lavandaia” [21]and “ho visto il mare” [22]. One of these from 1960 interested me in particular, it is an oil work on chipboard of the shingle at the River Piave [23]: It is practically all in the one colour and renders the idea of parched earth. The basic mournfulness is enlivened by charcoal lines that have a nervousness of gesture that is a desire to go beyond the conventionality of the atmosphere.

Shortly afterwards, in 1964, came his «Monotypes» [24]. Meneghetti himself recounts: «That year I had to work in an office. I had paints to hand and did some painting on the quiet in the office itself. One day a blot of paint fell on to my work-table. To clean it up, I covered it with one sheet of paper, then another on top of that and I realised that, with the pressure of my hand and the paper’s absorption, the paint mark changed. So I painted a figure on a third sheet of paper and «blotted» it with another. The figure changed completely and I realised that with sensitive pressure of the finger-prints, I could obtain chiaroscuro effects and variants in form.» Nothing out of the ordinary, certainly, but is it not curious that time and again Meneghetti’s discoveries come, not from indirect acquisition but from direct personal experience. We can speak of the «subtle tactile pleasure of Meneghetti’s hand [25], slightly trembling, with the leaf of paper over the matrix», and during this pressure, «the mood alternates its movements». There are moments when the artist perceives his own sensitivity, fevered and excited, that was to carry him on to work with effects of enfeeblement and an almost neurotic transparency.

The Monotipi in a way, are the precursors of the Radiografie [26], with the ink spreading out in magma-like areas, now clotted now dilute, like a living organism caught out in its own recondite movements. The pictorial quality is undeniable, enlivened as it is with a propensity towards society’s dramatic moments, or what used to be called social instances - the howl of Munch’s monster [27], the procession of demonstrators in all its compressed energy, the downcast coffin cortege [28]; , or an army of evanescent shades which [29] , in the manner of Balla, seems to be advancing into ghostly space. Here too is the jail [30], the run [31], the soldier [32], here is the crucifixion with its alternation of monotype and line drawing [33].

The effect is always that of a movement that starts with the physical and becomes psychological. It is no exaggeration to say that Meneghetti’s propensity to come out of the immobility of painting to try ever new roads, up to and including cinema, has existed from as early as those sheets of paper done when he was seventeen or eighteen years old.

This is a period of convulsed transitions. In 1964 American Pop Art had invaded the Venice Biennale and spread throughout Europe. It looked as if the season of the Informal was finished and that even the techniques of Abstract Expressionism had been overtaken by the «cold» oppression of consumer objectivity.

His surprising and mature another painting of the 1965: “I Baccalà” [34]. It remembers the “Neo-Figurative” atmosphere of that period.

At the end of 1965 Meneghetti did some graphic studies between Pop Art and Optical Art. There is a drawing of a woman with an effect of a distortion of the eyes [35], there is also a photographic collage [36]. His frescoes were coming out at the same time - six paintings in the ancient mural technique, the paint is granular, tactile and vibrant. He calls these «the lost walls.»[37]. In the reality of it, there is a sense of demolition, of exposure of the violated intimacy of the home, and even a kind of harrowing nostalgia for things lost and gone. Lucio Fontana, a master of the avant-garde, has the following to say, «This is a centuries-old technique that seems to be reborn under a hand which, in contact with new themes and conceptions, shows sensitivity to the problems and instances of the contemporary world.

click here for

"A DEEPEST AND SPONTANEOUS SOCIAL INSTANCE", edit by Lucio Fontana - 1969

But at the same time, it is these very frescos that mark the historical turning point from Material Informality, imbued with its tactile sensitivity, to new means of expression, nearer to the dimension of a technological and a mass-orientated world.» Young as he was in 1965-66, Meneghetti, in opening himself to the social in his painting, became part of the artists’ world. This was when the collages were born and he won a competition in Padua on the theme of the Nativity with a collage of dozens of photo clippings and work done in Indian ink, giving unity to the whole. This collage is based on dull greys only very slightly cheered up by melancholy lighting effects. [38]. Several months later, he won another first prize at the Pettenon Competition of San Martino di Lupari, with another photo-based work called The Snow was falling at Auschwitz [39]. The timbre here takes on tragic overtones with smoked passages (the cremation furnaces) and a barbed wire insertion that runs straight across the composition. This opening to the very experimental in terms of the collages, barbed wire, the use of a candle-flame, reveals a Meneghetti that is intent on reaching the highest expressivity going even beyond traditional media.

click here for

"Sir Denis Mahon's Epistle"

Historically, this was the time of great drug diffusion, there were the Beatles, pacifism, the Rower Children [40], and Meneghetti was turning out photographic assemblages of emblematic figure-motifs. He was using crushed-up paper and Indian ink, first splashing the paper with ink and then «cleaning it up» in various ways. The effect of this is disconcertingly up to date - reminiscent of some of Andy Warhol’s more tragic silk-prints, the ones taken from newspaper photos but more ghostly, even hallucinatory, in effect. In the centre of one of these, the artist’s eye becomes gigantic, in the Optical manner, roving around scenes revealed by the photo clippings [41-A] [41-B]. The 1967 brought a revival of Meneghetti’s monotype technique but with its adjunct of photo-collage work. At this point the image reaches its greatest sensitivity, dissolved into those washed-out greys that proclaim existential bitterness. The monotype is detached from any question of figure-work. What it becomes is very refined texture with only just perceptible signs, some manual, some, like typewriting, mechanical [42]. The impression is of a small, very precious papyrus rescued from the millennia. The images appear and disappear with a mobile, prehensile ambiguity worthy of Leonardo (the moulds, the mural marks and outgrowths, the vegetable micro-organisms) and Freud’s interpretation of it, with the vulture appearing out of St. Anne’s cloak [43]. In fascinating works like these, are the forerunners of the technique to be used much later, from 1979 on, for the Radiografie. The painting is like transparent, neurotic tissue, like a skin covering the underlying network of nerves. It is almost as if the artist wants to lay himself bare.

A LONG JOURNEY: "LE FAGOCITATRICI" OR THE SEARCH FOR THE UNCONSCIOUS

click here for:

"LOOKING INWARDS, LOOKING BEYOND", edit by Luciano Caramel - 1999

Meneghetti sallies forth in 1968 itself, aflter a long series of convulsed but closed-up researchings for a language. In Sixty-eight this Bassano artist was just twenty-one and there is no way of connecting his work with any precise current or trend of the time.

By that stage, Pop Art was past and assimilated and its Italian exponents, Schifano, Pozzati, Ceroli, Del Pezzo Angeli and Girardi, for example, had lost their bite. Cinetic and programmed art were not finding and outlet on the market Optical Art was on the rise but Meneghetti had tried it out, as a fashion, in 1965. Dorazio-type geometric abstraction was not picking up, there was vague talk of Arte Lucida, and the velleities of the keenest of the Avante-garde, such as Manzoni, Pascali and Pistoletto, had come and gone. In other words what Sixty-eight lacked at birth was a strong trend, and this to such a point that at the Venice Biennale that year nearly all the Italian artists turned their works round out of protest and then, perplexed, put them right again. Faced with the perceptivism exhibited at the Italian Pavilion, disconsolateness prevailed - nihilism, the «death of art».

But it was in that very year that Meneghetti tried to put ghe crisis into visual form by inventing his Fagocitatrici [44], (elements that swallow up others, like the phagocyte cells in the blooD] thus bringing a symbolic quotient to art, one that was hard, expressive, even irritated, but stayed within the medium of painting as image. One person who recognised this was the nonconformist Lucio Fontana, who wrote about «These monstrous, unformed tubes, alive with a mechanical life of their own», which absorbed, «individuals en masse into the black emptiness of their mouths» [45]...

Ambiguous painting it was, as ambiguous as its times but full of an essential fury that had very little in common with the malaise and uncertainties of its contemporaries, ever more ready to assimilate than to contradict and, in any case moving out of the strict medium of painting to plunge into the emptiness of ideologies. Looking at Meneghetti’s Fagocitatrici today, what is most striking is their impulsive peremptoriness, the dark violence of their forms, their merciless movement and the searing symbolism of their colours.

Meneghetti’s qualities by no means finish there, though: At the time, this might have been even harder to see, but in these Fagocitatrici as in subsequent developments of Meneghetti’s down to the works of today, there is an autonomy of hand that today is downright amazing. This is not, as often it is in post-war art, a matter of a «signature tune» repeated with variations, so tho speak. Here the quality is something more like an existential imprint, a completely personal message, one organic pulsation that is without parallel elsewhere. In other words, where the other painters of Sixty-eight were letting themselves be sucked into the vertigo of the unknown, to the point of dissociation from their own psucho-physical identities, Meneghetti had, and keeps today, only and above all unconsciously, a linearity of expression that goes on from Fagocitatrici [46] to Phagocyte Elements. Without for a moment losing itself, this quality of Meneghetti’s can break up, become shattered, it can transmute from analysis to synthesis and back again, it lets itself go and jumps ahead, now it is frenzied, now lyrical, now even melancholy. It in fact takes a grip both on nightmares and Utopias: it is hope.

Very often it is a two-dimensional way of catching form and breaking it up, alternating its sinuous curves and dry corners without losing its own particular organic nature. It is enough for us - and at best done in rapid sequence - to observe the various paintings, starting perhaps from the Monotipi of before Sixty-eight [47], and come down to the luminescent nerve-nets of the Radiografie of the Eighties and Nineties [48].

What seems to loom up in front of us is an amorphous mass, puffing out as if there were yeast in it, moving. Holes seem to gape out of this: material sucking itself back in and livid tones over yellows and magentas accentuating this feeling of uneasiness. We are in 1968 and everybody knows what was going on then, but who among its artists has managed to communicate a malaise that all but turned the stomach and keeps coming back up in a series of regurgitations? Who was capable of taking that feeling and giving it the imprint of a great cultural turning-point together with a general disorientation? I keep going back to have another look at Renato Meneghetti’s painting - one of the many - entitled "Fagocitanti I" [49]- and refeel the echo of a time that is still impressed on us all. His work sums up a situation, it encapsulates a moment in history and gives it, a categorical projection we could well call universal. The artist becomes an even terrible means of self-knowledge. He it is who lets us hear our heartbeat and thus come closer to the mystery of the life all around us which, now and then, vouchsafes intuitive scraps of hidden truth. The black holes of our universe can be seen in the formless, viscid masses of these Fagocitatrici. [50].

"«Can’t you see them? They are spores that go around in the air, lurking [51]. They land on an individual’s skin and turn into illness, leprosy ...» I am scared to even touch these paintings, they have got phagocytes and their artist well knows what these phagocytes are. I, who know nothing to speak of of biology, realise only that their common Greek root is faghein, to eat: in other words, these phagocytes «phagocyte» us, they eat us up. They become an illness and this painting symbolically represents that syphilitic scourge, that threatens to envelop and «phagocyte» us all. Bad digestion?

You really can enjoy yourself with Renato Meneghetti. Of course he has always been just a bit self-centred, narcissistic and, but very acceptably, megalomaniac [52]. Are these really faults? I have been to his Bassano studio [53]. Its a vast shed with his paintings, hundreds of them, ordered against the walls. The man himself is full of life - energy pulses within and yet does not stop you being aware of his inner perplexity, doubt and uncertainty. All these Fagocitatrici that nest in the very paint at once upset and excite him and he says, «What painting is for me is a conveyancing that lays society’s sores bare. We are all eaten alive, all but sucked into the phagocyte mechanisms of the system. You watch these phagocyte elements: they move around on the canvas, but they also get into us. They turn us into cogs with no capacity to think or act for ourselves. My work is not a hedonistic game, an end in itself: I paint under the stimulus of organic cellular pulsations. My work, then, strains to make that endemic sickness that we nurse within, visible. This is why, and as early on as 1968, I invented the Fagocitatrici.»

«That was the year I did my military service. I struck it lucky immediately When I said I was a painter, the colonel asked me right away for a portrait. I did it splendidly, with a sword. From then on all the Officers wanted me to paint their portrait: I practically became the court painter. In this way I could also get on with my own painting - the kind of painting I felt was mine, and this was a new leap ahead.»

Meneghetti, in fact, did several landscapes during the first part of his military service. He not only felt the need to get back to the figurative, but also to work in purely pictorial terms. Some of these landscapes are interesting in that they are like geological stratigraphies [54], nature seen from inside and out. There is a strange gentleness in the immersion of this man in organic darkness that symbolically becomes psychic darkness. But the colour is symphonic and the tonal shading splendid.

The Fagocitatrici are virtually contemporary with these landscapes. They too come from his term of military service when as a man and as a soldier, Meneghetti felt depersonalised, imprisoned within a machine that he could not fight. Then, as now, the broad lines of Meneghetti’s message is that society destroys the individual, it swallows him up like a phagocyte, it takes away his autonomy, his freedom and his true capacity to create. Undoubtedly from the stylistic point of view there is something of Pop Art, still in vogue at the time, with two dimension treatment, clear outlines and industrial-type colours.

click here for an essay about "Phagocytation" "THE SECRET STRUCTURE", edit by Laura Cherubini - 1999 |

The movement from Fagocitatrici machines to Phagocyte Elements [55] and vice versa becomes Meneghetti’s Leitmotiv in all his painting at least up to the mid-eighties. Lucio Fontana was one of the earliest to understand and appreciate the new paintings that, from 1968, Meneghetti was producing. He writes, «In these every barrier between the real and the unreal, the conscious and the subconscious has been broken down and these coexist, in an atmosphere of rarefied and extremely personal vitality.» and again, «In all these works there are machines, monstrous and formless tubes with a mechanical life of their own. In the black emptiness of their mouths, they twist and absorb individuals, who, en masse [56], get mixed up with the shapeless piles of rags or brushed by a weak breath of vegetative life.»

That these phagocyting machines come within the discourse of alienation of the individual in consumer society, as Alberto Folin has pointed out, and that these «diabolic agents» that corrode everything are, principally. Money, Sex and Power, is fairly clear. In the Meneghetti's theory the money is what “phagocytes” us. The money becomes the “Maxima Phagocyte” [57], and who uses it is “phagocyted” from this evil instrument. This concept is explained in the installation entitled “Nulla Vita Ex Hoc Pane” [58-A] [58-B]. Anartwork against the power of the money as cause of wars, genocyds, ecc. The thought is tragically simple: the money creates a “re-cycle” [59]: NO MONEY NO WAR – NO WAR NO MONEY.

All Meneghetti’s painting speaks - and often shouts - symbolically. The images acquire a strong symbolic quotient even if remaining for the most part obscure since, rather than being representative, they are allusive or at best evocative. There are times when the artist seems to want to tighten his grip on this monster of his own creating but rarely, in the earlier years at least, does the «phagocyting» turn to the subject in itself. By its very nature it is significant and at the same time ambiguous. These machines grow out of all measure: they twist, swell and dilate. But they also shrink like black holes, condensing the folds of formless bodies [60], becoming simulacra, horrendous totems, fetishes where the organic and the mechanical are as one. This Fagocitanti series is truly splendid and at a distance of thirty years holds up surprisingly well.

What strikes one is Meneghetti’s cohesion of style. At least from that happy 1968, and for many aspects even beforehand, Meneghetti has a temperament that, whatever be the form he is expressing, he does it with every bit as much autonomous individuality as a fingerprint. We can recognise, at the beginning as well as the end of this cycle (but is there really and end?) that certain spark of peremptoriness in the stroke, that trapezoid or at times rhomboid way he has, the way the pieces fit together, the continual use of chiasmus and formal intersection, the alternations of full and empty, above all that spectral and ghostly sense of the image, be it compact or broken up, entangled or spread out. Meneghetti carried this phagocyte discourse on for five years and his painting, always in two-dimensional inlays at once well put together yet distorted, keeps its eruptive dynamic strength. How do you define this kind of painting? I would place it with a certain organicism that reigned at the time, but it would be hard to align a British artist like Alan Davie with an American like Roy Lichtenstein. Everything here is tight but fluid, dry and soft at the same time, ghostly, always spectral, but conceding nothing to the Necromantic. These machines suck in, annihilate, suffocate and crush. These tubes that every now and again are to be distinguished, set a kind of organic mechanism before us, one that brings together organic, vegetable and mineral Francis Bacon, albeit in a different way, was working along similar lines, but Meneghetti’s stroke and form are unequivocable.

After these five years, Meneghetti had reached fame, was gratified by it if not satisfied, so one day he took one of his paintings, called Extermination Hypothesis, and scrawled the word «Basta» [61] (enough) across it. That was in 1973 and thus the series came to an end. He explains:

«I decided to start a new page, to blow up my phagocyting machines. I continued on the way of symbols but I got to the point of shattering forms, dissociating them. The image thus lost that monstrous compactness.» Little by little, other paintings arose, similar yet different.

This cycle, realised between 1977 and 1978, and entitled Phagocyting Elements, is more intelectual in approach, less instinctive. The historical change that art was undergoing could be felt in the air - from the object in itself (Pop Art) to its intellectualisation (Conceptual Art). These elements, dissolved in the air [62], floating in an amorphous space, are what become, as we said earlier, spores that cling to the skin, corroding, cutting in, emaciating and putrefying it. Meneghetti had one basic fear in those days, of being misunderstood, becoming the object of mere formalistic, if not hedonistic satisfaction. The fetishist technologies obtaining at the time provided the chance for explanations that were serious and at the same time ironical - or better, cynical. In these compositions on phagocyte elements, often broken up into a convulsed and desperate shrapnel, he often added hand-written messages [63], for instance, «Gears of mechanical advancement of the Ego towards the blades of aspiration.» or, «Jointed vacuum tube: this can be trained on anyone present within an angle of 360¡» or yet again, «Pre-reducer: this reduces the ego to pulp before the ultimate phagocyting.» Even these explanatory notes come into the language - albeit irritating and misleading - of the media. Science seems to be coming to the ais of a system that, more than ever, is staking everything on Money, Sex and Power.

At this point, in 1979, a phase of passage begins in Meneghetti’s language. He is searching for new means of expression. Does painting still serve? It borns the first x-ray [64]. This is when he takes human-sized models and sets them up in a scene that resembles a painting. But he has made a clean cut with painting, «Man returns,» he says, «to his human form. He becomes sculpture, motionless and apparently absolute, like a classical parameter. But he does not escape from phagocyting for all that. The monster swallows him up.» We see these models, black ones and white ones [65], marching ahead through the night like sinister simulacra. A head appears here, and arm there. The individual has definitively lost his personality even if deluding himself, presumeably, that he has gone back to the natural state. The title of one of these series is «Human Bodywork» [66] andthe title is significant. One model’s head seems to have been cut in half [67-A] [67-B], there is a mirror reflecting the profiteer who comes onto the scene with the other phagocyting elements, he too having been phagocyted. Clearly, Meneghetti is using emblematic material from both Hyperrealism and from the Conceptualism of Pistoletto. This is always done autonomously without slavish copying, above all in direction that stays his own.

Thus, almost at the same point, sculpture gets on to canvas and comes back to being painting [68]. This is one of Meneghetti’s most fascinating cycles. From 1981, the models’ faces are reflected in photographic emulsion [69], painting becomes more refined, metaphysical, in the air. The characters are maybe those of the great consumer world - there is Mastelloni [70], David Bowie [71], Ivan Cattaneo [72], the leader of The Kiss [73], and their blurred faces refuse psychedelic lighting, they take refuge in the grey half-tints with abstract, unreal colourings. There is something like leprosy on the faces, or at least a sad, melancholy veil of hopelessness. Over this washed out atmosphere swarm the phagocyte symbols, like flat tongues of fire in continuous movement. You can feel that Meneghetti is coming near to the film world, as if the strictly photographic one was no longer enough. Look at the edges of these negatives, the oblique cut if the photos, the black veiling. There is an effect of cinema stills [74]; He arrives at complete depersonalisation of the individual, of the ghostly, pictorial mannequin, metaphysical suspension, submerged, larval and therefore enigmatic and ambiguous.

This is where the poetics of hiding and veiling [75] things comes into force, so well described in a learned article by the sociologist Ferlin. In a 1981 exhibition at Bassano, Meneghetti was showing opaque, totally amorphous painting that the public was invited to «unveil» using a rag soaked in solvent. In this way, casually or in any case fortuitously, the underlying photographic emulsion, with its human figures, was revealed. As Meneghetti said to those visiting the exhibition at the time, «We do the work together.» [76-A] [76-B] [76-C]. In one of his highly learned essays, Roberta Guiducci sets out by recalling Freud, «To be once again, as in our own infancy, our own ideal... is the happiness that mankind promises itself.» But disappointment comes hard on its heels: virginity in our actions - in discovery of the image - is illusory. As Guiducci remarks, metropolitan neurosis, that shows us these grottesque mannequins, shorn of history, psychoanalised and decodified, «catches us out as phagocyted, not to mention phagocyting.» Hence these pictures, «on the surface of which appear faces, washed out as is forgotten and covered with the patina of time, simulate an unreal future. And Guiducci quotes Massimo Cacciari in this, «Posthumous man runs through an infinite series of masks and does not stay with any of them»; thus the exercise of discovering what lies underneath like the sinopia drawings under frescos [77-A] [77-B] [77-C] [77-D], once more turns out to be based on lies. And phagocyting oppresses us all.

75  76a

76a  76b

76b  76c

76c  77a

77a  77b

77b  77c

77c  77d

77d

From this point, Meneghetti, without actually abandoning painting, comes out into the fray with a series of photographs published in 1982 in a book called Insania, as unusual as it was provocative. [78] He says, «It was a risk, but one I had to run. I was looking for a medium that was more immediate and pungent, stronger. I was the one who became the subject and object of the phagocyting».

Meneghetti paints his own face, he camouflages himself [79], subjects himself to lighting and colours, he deforms himself, gets into some even horrendous disguises [80]. He becomes the actor, the masked player, the fetish. Symptomatically this volume’s opening quotation is from Nietzsche: «Who are you, wanderer? I see you going on your way, without protection, without love, with an indeciferable look. You are damp and sad as a plummet that re-emerges into the light, unsatisfied, from whatever depth What were you searching for down there? With a chest that doesn not breathe, a lip that conceals its disgust, a hand that by now only grips slowly: who are you, what have you done?» These are the queries of Meneghetti the wanderer, with his bitter wrath to sustain him. The exhibitionist histrionics here is only a desperate desire to know himself and to know. The artist identifies himself with his own cynical jailers: «I too become Money [81], Sex [82], Power [83] but in the end I am also changed into Christ [84], that is hope».

But are images enough? Meneghetti himself felt, «the necessity to translate these images into sound, just to broaden possession of the medium and thus my own force of expression». The Padua University Centre for Sound Research put computers at his disposal and the emotions of Insania were enriched by sound. «I am the one, it is always me, who put my feelings into concert form». The system itself is ingenious: it is based on musical scores by Meneghetti and «tuned» for the computer, and in 1982 this same «Concert with images» was presented at the Venice [85] Biennale festival of contemporary music. And yet Meneghetti proves insatiable. «I had the sound-image, what I did not have was the action» Hence the film, Divergenze Parallele [86] was born, to dialogues by Guiducci. «This is the story of my inner life,» says Meneghetti, «with the contasts that come up when the artist becomes entrepreneur». In this film of one hour and forty-eight minutes, there is a chorus of crystallised mannequins - sound and image again. This film was a great success and was shown at the Venice Rim Festival the next year [1983] [87] - another recognition from the Venice Biennate for Meneghetti’s creative qualities.

click here for

"GLORIOUS: ELEMENTS AND DISCIPLINE OF VIOLENCE", edit by Gregory J. Markopoulos - 1982

Theatre coulld not be far behind and it was the Municipality of Padua that put on a performance «under the eye of Giotto», for the "Patavanitas" event, [88] at the Roman Arena with its grandiose stage, of 60 metres across and 80 in depth. Despite puzzlement on the part of some, there was great interest crowned by the award of the «Fenice d’Oro» prize for the best theatre performance of 1985. These forays into films, theatre and music out of the world of traditional painting are in part the fruit of a multimedia dream of Meneghretti’s, a desire for a global means of expression, in the Futurist manner. But it also has its historic parallels in other artistic fields. There is Conceptual Art that turns to installations, there are the Happenings, Land Art, Minimal Art, Fluxus, Poor Art, and there are artists such as Kosuth, Cage, Beuys, Paolini, Andre, Nauman and Merz. All of these use consumer objects, natural ones, forms and sounds, actions and thoughts, in a kind of Utopian syncretism that starts out from Nature to arrive at the most refined levels of cultur. In Europe and America, the yers from the Sixties to the Eighties really are marked by this inebriating flight, although often the results are the prostration and nausea typical of post Sixty-eight depression. Meneghetti is there though, he senses the situation and enters this great multimedia concert.

click here to read more:

"THE COLOUR OF THE BODY", edit by Elenea Pontiggia-1999

RENATO MENEGHETTI: "BODIES OTHER", edit by Flaminio Gualdoni - 2000

The New Phagocitings arrive with a photographic basis taken from comic strips, formula 1 [89] racing cars, scenes of pornogaphic eroticism [90], TV shows, a basis of status symbols, consumer society applying pressure from below. The phagocyting elements flash like sparks of violent colour. There is a kind of prelude to death (the connection with the 1995-6 Radiografie is very clear) with the patting technique nearly always funereal, ineffable sadness. There are depersonalisations of work, with workers in gas-masks [91] and authentic robots, slopping in an atmosphere of grey squalor. Even the hieratic images of women, in their Nefertiti-like absorption [92], in an unreal light, are nothing other than tragic masks, emblems of the mistaking of Beauty itself. There are faces in ghostly prey of hallucination, fragments that associate and dissociate, come together and seem to disappear in the machine of obsessive consumerism. The monotype makes a tortured comeback with mechanical and organic waste trying to get out of their ghostly fixity. There are more of the red or black flashes of the Fagocitazioni, now more like writings from beyond the grave, painful lacerations [93]. Sometimes a tragic mask, as in Insania, comes out of the murky background and music makes its appearance with visual images of scores (what Boulez called the «beauty of the score») and strange musical writings [94] that seem as if they are psychic footprints. The quality of Meneghetti’s style, his particular sign, is always evident, though. Even when it is a matter of images taken from consumer pornography [95] (and this is one os his larger series) the blackish backgrounds swallow up and all but obsessively decompose sexual pleasure; bringing it close to death. These images are nearly moral apologues. In 1984 came the decoupages [96], i.e., a rediscovery of the image through ripping and obliterating. Curiously enough ripping up, with the painful edges it produces, brings back the Fagocitazioni cycle, and a surrealist hasard that consolidates itself in the organic confermation of the artist. Then come the broken mirrors [97], and again a return to pure painting [98], even neo-primitive. The photographic part od always used in differing ways [99] - the poetics of a classical fragment, recomposed. [100]

By now we have reached 1985 and what we might call the Fagocitazioni phase ends here. Meneghetti, with his frenetic activism, turns to design [101] and makes an international name for himself. He works as an architect [102] and a writer, he manages no less than ten journals [103-A] [103-B] [103-C]and moves with extraordinary ease through the world of contemporary creativity.

click here for

"EPIGRAPHS FOR LIGHT ONLY", a cura di Marco di Capua - 1999

These are not years of pause, though, but for rethinking, experimentation, waiting in trepidation till the point that the paintings of this latest phase, that of the Radiografie, take shape. [104]

101  102

102  103a

103a  103b

103b  103c

103c  103d

103d  104

104

LOOKING UNDERNEATH: RADIOGRAPHY SOMETHING NEAR TO THE SOUL OF MAN

click here for

"X-RAYS OF A DESTINY", edit by Gillo Dorfles - 2000

We are not used to seeing orselves and that above all in how we are inside. And still, the skin is a delicate thing, fragile, at times almost transparent. Radiography is a scientific means of introspection and helps us in that it starts from the physical, it doesn’t stop there. It is us we are looking at. An artist has something of the same calling: he too looks within. Meneghetti, from his early Monotipi of the sixties [105], even working spasmodically, has never given up this vocation. He too looks beyond the veil, underneath the purely material, beneath the sensitivity of the skin. These early Monotypes were by way of being a second - or third - epidermis beneath which there was the pulsing blood, the network of nerves, the musculature and, barely perceptible, the bones. This, as of 1981, developed into his Radiografie (X-rays). These enlarged photo emulsion works [106] show up what Meneghetti called “phagocyte elements” in the form of tongues of fire, assailing the helpless, X-rays became Meneghetti’s artistic “actors” from 1981 on, showing all parts of the body, shank-bones, jaws [107], esophagi [108], skulls - even gullets. By 1985, Meneghetti had had enough of the phagocyte discourse and the Radiografie took first place [109]. The earliest of these were enlargements in the original shades of grey [110] on the plate. Then he started using colour. This was never and arbitrary business, it followed the form of the original with its nerves, interstices, expansions and dilations. Tone thus arose from within the forms and the result could well be called illuministic in that it has the same effect as the lighting on a radiologist’s panel, only here there are extraordinary maps, fantastical pathways and improbable but fascinating adventures of the spirit.

This is how the Radiografie, above all the latest ones, should be seen - as new worlds, as the scan of the unconscious. There comes a moment when the anatomical side disappears [111] and the painting sends us sailing into distant, stellar seans and we barely notice that these spaces are not unfamiliar, but come from within ourselves. And we begin to wonder, is this not the discourse thas has carried Meneghetti’s work ahead from the start, in all its continued stubbornness and anxiety? The technical instrument is different, the expressive finality completely the same. It is over all these last thirty years in fact that the essence of Meneghetti’s art is to be gathered. It is an exploration of the woundings and windings in man - an introspection done with the scalpel to see what lies beneath, an obsessive search for individual autonomy. It is a fascinating adventure and all the more so because the one who is taking us by the hand beyound the Pillars of Hercules is a sensitive multimedia artist. He is frenetic and inventive, works in harmony with the historical world but is in perfect accord with the obscure pulsing of the psyche. Slowly, with caution, let us attempt to approach these new horizons that Meneghetti’s painting, in the shoes of the radiologist, so to speak, is trying to show us.

Look at one of these X-rays of a hand [112]: acid-green east up the digits that seem to be reaching out in a spasm. Out from this hand comes a paintbrush painting a white line that stands out on the surface with an almost material consistency. What does this mean? It is not only a metaphor of painting - fleeting mark on the sands of time. It is rather that basic confrontation at the roots of all Meneghetti’s work, the confrontation between life and death, where the funereal impact of the X-rays contrasts with the vitality of the gesture. This all takes place over a murky black back-ground and there the great chess-game is played out. The mediaeval memento mori come flooding back to us, tragic, and here and now we begin to learn ... the sense of sight - the feeling of life even, is not enough any more. From now on every image becomes a symbol and every symbol alludes to the existential tragedy within us. The earliest picture taken from X-ray plates by Meneghetti dates back to 1981 and is almost reminiscent of an imprint and a shroud. What appears before our gaze is a child swathed in fine grey veilings through which the X-ray machine shows white bones. The head is abnormal compared to the torso [113]. The figure is spectral, of tragic grandeur. What strikes the observer, though, are those fiery tongues - Meneghetti’s “phagocyte machines” of old - and these seem to be devouring this bodily magma to the point of getting into the very brain, like and evil disease.

And once again the dialectic of contrasts comes up unmistakeably. To the washed-out pallor of the film comes the flash of life of painting. What this atmosphere calls to mind is the smoky atmosphere of some French films from the end of the thirties, such as Marcel Carne’s Quai des Brumes and Hotel du Nord. The black and white of these films, already imbued with melancholy, becomes further drenched in the rancid feel of the X-ray, and the consequent shudder it produces could well remind one of Bergmann’s Seventh Seal, and its famous chess-game with death. There is something peculiar in Meneghetti’s work, though: it is ill-at-ease and that gets under the skin. This child takes on the dimensions of an extra-terrestrial, an alien, metamorphosis swelling up and Kafka is not far off.

Sometimes the image comes frighteningly close. A detail of a dental arch seen on an X-ray [114]makes man’s very physiognomy a monstrous thing. And yet this artist does not confine himself to distancings and close-ups or combinations of elements nor only to evocation of these ghostly mists. His lively hand colours them: the need to paint is too strong. Today we are seeing some of these works of the eighties retouched later with new eyes. We see the garishly bright colours - the grotesquely flaming red lips [115] on the grey skull, the eyes encircled in black with a gob of yellow at the corner. This is the period when Meneghetti comes nearest to Warhol, but does not abandon those veinings that run beneath the skin amidst the now-calcified bones. What does the eye see beyond this? An aerial field-survery? There, “down below”, among the shrapnel of the bones, is the crater of a sudden bomb explosion [116]. The lighting reflects flashes of terror. Trying to “see what is hidden beneath” the skin is something that has always preoccupied mankind and not just for the actual bones and muscles, the subcutaneous fat, cartilages and nerve network that spread out beneath the epidermis of this wonderful “machine”. He has always desired intuition of what lies deeper still, the motive force, the soul, that breath of the primordial wind, that hidden respiration that moves things, that exquisitely spiritual essence. Man has rummaged and searched, with curiosity and enthusiasm, not to say passion, for centuries, millennia even. Art, that is to say the lyrical intuition of knowledge, has often brought us close to this mystery but one thing is sure: the moment we try to get near this great discovery, it eludes us. What, then, are the finer instruments necessary at least to be able to aim at this sublime purpose? What role does art, and painting in particular, have to play in it? Is it only a gratification of the senses, ineffable pleasure? Or is it almost a scalpel which, slipping under our skin, indeed lets us see “what there is underneath”?

Elémire Zolla cultivated the exotic and he warns us that once we have managed to comprehend the surface area of a work of art, appreciate its textures, enjoy its balance, the propriety of the tones used, we are only at the start. The real struggle has yet to come, for revelation of its intimate truth for which there are no words. Meneghetti’s work is to be seen like this and above all in the later part, the Radiografie, as a fine membrane that, neurotically, unveils what is underneath, the “intimate truths” of man.

click here for "BEYOND THE NAKED EYES", edit by Vittorio Sgarbi - 1999 |

FROM X-RAYS TO ART: THE REDISCOVERY OF MANKIND

The outline of a jawbone [117-A] [117-B] gets more and more gigantic, closer and closer, it threatens almost to take us over in its abnormal enlargement, then it stops, motionless. This could be traumatic and our mind tries to keep control, but the image has managed to slip into the psyche. What does it turn into? Maybe a landscape bathed in every yellow light and blurred by the veining the the lens seems mercilessly to be imposing as clouds. Then another jawbone appears, that too a radiographic enlargement, beside the first one, but reddish in colour. We examine both of them: they are identical, but the colour lends a different interpretation to each. The yellow landscape, now turned red, has become overcast, stormier, more tragic.

These are two atmospheric moments that become psychological ones: The right-hand mandible, with that overcast red and its frightening sliding and threateningness, almost seems to come from within us. And yet the objects are the same so we alarmedly begin to wonder, is this cloning? Proserpina is the same: there she is ready to go out to greet the Spring, and there she is again, going back into the underworld. What Meneghetti is saying to us in his painting is how similar diversity can be.

Are Turner’s clouds the same as Constable’s? The fact that it is colour that is used to modify the impact of one image makes one think. The cosmic space that the dilated image of a jawbone - or for that matter a femur or a digit - can conjure up, ties up with the very depth in our brains - the abyssal mechanisms that regulate thought. Form and colour loses any autonomy and set to speaking another language. Freud is there, digging away with his invisible scalpel. There are even times when we losetouch with the object in the X-ray. Be we scared or all too willing, we are plunged into a sea of melting colour that goes beyond form, clotting and spreading, seeming to coagulate into lumps and then to become as free as a breath of air and that is when we see - or better “see” rivers, lakes, streets, skies, seas and hills. [118]. Or we focus in and are in the world of histology, amoebas and sperm-cells [119-A] [119-B]. Macrocosm and microcosm end up by coinciding, art has carried us beyond mere physical space and time. This is the ectoplasm of the scare [120], but we get familiar with it and see these bones, vertebrae, cartiledge and muscle with another eye.

Basically this is what happens in the art of a great master like Joan Miro. In Meneghetti, as in Miro, iart forces the artist towards what is “beyond” and it is the dimension of the primordial, primary senses, and all that the dawn symbolises. Miro’s ovoid, egg-shaped, form takes us back to the origins, and there to find an unrestrained joy, avid and with a panicky sense of explosiviness. A good look at these Radiografie convinces the observer of Meneghetti’s impressive lucidity. Every bit as much as for a doctor, an X-ray for him is an instrument trained on the fact of “seeing beyond”. The paint, with its applications, fitting in, agglomerating, absorbing and eating up the image, has its function. It serves for contrast, to bipolarise the image. It is like a slow deforming agent, a semantic transliteration that image painting [121] like that of Fuessli, the late period of Goya, but also Max Ernst has always pursued, even to the edge of hallucination and psychic upheaval. Only, with Meneghetti, the basis is not literary fantasy, like the monstrous insect of a nightmare, but the science of radiography.

On the basis of this science, the artist takes the image and reconstructs and reproposes it as a larval fabric that, at the outside is like an exquisite floral decoration [122]. Who cand not be taken aback by the subtle nuances of a finger thus chromatically lined and veiled? The transcolourings done in shocking pink and metallic brown [123] have an amibguity that is not so much aesthetic but existential.

It is as if we were listening to Mahler’s Songs for the Death of Children, the Kindertotenlieder, with Meneghetti producing something very much in the spirit of Finis Austriae sweet, sickly-sweet music that spoke of the oncoming war, the slaughter, with the artist catching the last twitchings of a pleasure that was to end. We can feel it, this is the atmosphere of Klimt and Schiele, in a suspension of time that is on the edge of the timeless abyss, pleasure joined to death, Eros and Thanatos, the skeleton drawing the nubile young girl into its arms.

Ambiguity: and Meneghetti who cleverly works on several levels at once, as if to upset all the known, traditional mechanisms. There are times when the eye does not distinguish image from background. They entwine and alternate. And so it is with the paint textures, sometimes granular, others rarefied out. Physical and psychological conditions are in a state of change and painting ends up by being an extraordinary liaison between knowledge and psychic mecchanisms. A kind of Gestaltpsychologie and hence a scientific instrument in itself - and much more profound than radiography. Gentleness and violence reverse their roles, the tragic pallor of death revives in the breath of colour and the bracing brushstrokes [124], skeletonic hands brush against each other, even touch [125]. But what is this, an act of love or a gesture of repulsion.

Certainly Meneghetti’s scalpel shows us what is beneath the human epithelium. He probes deep and hence puts us into touch with human depths. These cramped-up limbs, the bones revealed, the nerve networks barely visible are all a spasm, a call to life. Painting always has something to communicate: this tome has it been grasped or denied? The image’s framework, opened by the colour, attacked by acids, seems to be coming apart at the seams, worse, putrefying. Beauty, if one can call it that, is life itself bursting out, not a death but a birth. There is an enlargement of a human gut [126], formless tubes that hark back to the period of the Fagocitatrici and inveigle us into their moving contorsions and meanderings, and the vestiges of a palate, a tougue [127], and a dental arch become an enless landscape, turned towards the absolute.

But what happens? Bones become clouds and howling humanity emerhes from these clouds [128]. To hark back to Joan Miro for a moment, the simple becomes extremely complex and vice versa. There is something of Leonardo’s metaphorical fantasy that took mould and mud and made horses and knights of them [129]. It is still from there, from Nature and introspection in the inner landscape of the human being that the gigantic shadows of the imagination come, primary sensations from which, as we have said, Meneghetti’s adventure sets out. Nietzsche said that artists are not travellers, they are wayfarers, that they go according to each case, and each time discover life’s wonderful facets.

He has always been aware of the multi-valency of the image. One has only to took at his Insania, where he makes himself the protagonist and interpreter of misinterpretation. Every time, we take up his stimuli and conventional archetypes, we recognise a head, say, or a cloud, a rock, a tree, maybe a scarab-beetle, and he is the one who stage-manages it all. And with that we come to the fact that these works are Meneghetti’s masterpieces. There are two large heads in profile, done in different colours [130-A] [130-B]. This is splendid painting which does not overlay the X-ray but is conciliatory to it. The green enters into the flesh of the red and the brown follows its mysterious way within the blue. And at last we see, that is recognise, the image. We see across the art, overcoming our own conventional mechanisms. At the same time, we see “beyond” as it were, we are at the artist’s mercy. He shows us the lower curve of a jawbone and we with a sly push, we can also see a slice of water-melon [131], a pumpkin or a kiwi [132]. The stage-artist, as does Picasso, takes us wherever he wants and so does Meneghetti, and did in his theatrical, musical, film and “happening” experience in the past. The fantasy landscape he gives us with this X-ray, is no longer ridden with ancestral fears, it is a discovery of the world. Friedrich climbing the white cliffs and finally “seeing”. Art takes on something sacred: it is a totem. It is real and unreal, object and ghost, material and spirit, life or death. And behind moves the pitiful teagic simulacrum of man.

click here for "THE SOFFERING MUSE", edit by Duccio Trombadori - 1999 |

SINCE 2000 MENEGHETTI’S X-RAYS HAVE BECOME GREAT INSTALLATIONS.

click here for

"RENATO MENEGHETTI AND GLOBAL COMMUNICATION", edit by Pierre Restany - 2000

In these last years, from 1998 to 2001, Meneghetti has developed the discourse of his x-rays by linking them to other works or installations in an organic project. In the large-scale exhibitions he has produced in 2000 (it will suffice to cite the exhibiution at the mammoth Mole Vanvitelliana in Ancona [133] and the other sensational installation at the prestigious Palazzo della Ragione in Padua [134]) he has created a dialogue with historical ambiences giving birth to extraordinarily suggestive works though always taking the radiographic plate as his point of departure.No mannerism therefore; no slavish repetition of motifs: rather a continuous “in work” creation.

New worlds; hitherto unseen perspectives; utopian flights; and, at the same time, close adherence to the scientific data contained in the image (“beyond the eye”). Since 1988 the x-rays [135], ultrasoundographys [136], scintigraphy [137] and other medical evidence [138] from which Meneghetti draws inspiration for his more recent works have not only employed humans and animals [139]. His elusive symbology has broadened its range to include, for example, x-rays of wood (“the soul of the forest” [140]), evoking surreal landscapes. The variable grain of wood has given rise to land or marine views, at times nocturnal, immersed in mists or weathered by the wind and the direct sunlight. These works are among the most astonishing. The point of departure is almost unrecognisable, so much so that the image acquires a life of its own alluding to something never seen before; something absolutely unexpected.

133  134

134  135

135  136

136  137

137  138

138  139

139  140

140

The refined graphic and chromatic solutions [141] – as has been pointed out by the critics – offer a new allusiveness that can be described as cosmic. The huge expanding tidal waves [142], the biological concretion, the imaginary transparencies, that sort of magma that overruns the image leaves us dumbfounded. Colour becomes light, air, and immaterial dust; and at the same time portrays the destruction of corpuscles in space. Though with a different language and technique Meneghetti comes close in these works derived from wooden material to the tormented symbolism of Munch at his best, when his painting was consumed and undone, totally tortured and reduced to pure fibre dispersed in the air. In other words the landscape becomes the magma of the soul.

From these works originating from wood x-rays, dated 1999, Meneghetti has drawn inspiration to continue his exploration of the primary elements: earth, air, fire and water. Thus we have the sculptures in terracotta [143] and painted cottons; created in installations that were so striking especially in Ancona and Padua. These are large sculptures (several meters high) that recall the form of a palm, with typical circular segments (“Vertebral parallels”). The evocation of the x-ray here is brought to a level of psychic sublimation.

The cycle entitled “Terra e aria” (Earth and air), shown at Padua in 2000, becomes a framework of the body: the chain of vertebrae evokes a parallel between spine and plant; creating images that evoke “petrified oases ” behind which x-rays of human anatomy move. At times an interpretation is urged of “columns of smoke and chimneys”, putting “the harsh and immediate memory of sacrificial pyres or even the crematoriums of Dachau [144]” on show (“Aldilà dell’occhio Dachau 7 a.m.” “beyond the eye Dachau 7 a.m.”). Towards the top these “spinal” columns cracks , they open, almost a testimonial of a pain that transfers itself from the organic element to the very flesh of human kind. Whoever – visiting one of Meneghetti’s installations– walking within these “speaking” forests, has the impression of being inside a phantom “city of the dead”, where the columns open in cracks [145], furrows, cartouches [146], natural releases and magic fissures [147]. It is the breathing of living material, creating a sudden union between archaeological artefact and the testimony of a living entity.

In the loggias of the Palazzo della Ragione, in Padua, (“Omaggio ad Akira” [148], “Tribute to Akira” 2000] were also included installations of cotton carrying human imprints that moved in the wind in continuous variations of indistinct forms and colours: an evocation, amid a fourteenth century ambience, of the “sign of Akira Kurosawa”. Here too the x-ray is the submersed base from which Meneghetti began. The plate is no longer static: it moves in the air; rolls in the wind, endures the endless affront of the light provoking unexpected changes.

Here are the “Trasparenze”, (“Transparencies”) another cycle that includes x-rays crossed, in their particular transparency, by light, always in the context of an ‘in-space’ installation. What is striking here is the symbiosis that is created between refined aesthetic composition and impressive symbolic suggestion.

The anatomical forms from the x-rays float ghost-like in the air (“Gerusalemme, Gerusalemme”) (“Jerusalem, Jerusalem”). [149]. The Padua exhibition entitled “Sull’orlo del terzo millennio” “On the edge of the third millennium”, was greeted with enthusiasm by the most influential critics. Gillo Dorfles has defined Meneghetti’s x-rays as “the only new event to have occurred in Italian art over the last twenty years”, Achille Bonito Oliva has decided to make his observations into a volume to be published soon; as has Vittorio Sgarbi who spoke at a public conference at Palazzo della Ragione of “an estranged beauty on which the breath of the psyche has blown”. Moreover the exhibition was an exceptional success with over 20,000 visitors.

Thus we reach the “stained-glass windows” (“La struttura segreta” “the secret structure”) [150], the most fantastic example of which is the transformation, carried out in 2000, on the windows of Palazzo Passuello in Bassano del Grappa. The building in Art nouveau style dated 1907 is the artist’s studio and houses the “Arts from Science” foundation. Intensified by the light from within the windows show transparent parts of bodies: “transfigurations of that which is invisible in nature”, a metaphor therefore of a script that becomes “meaningful” in so much as it itself is a description and portrayal of human bodies. The effect is extraordinary especially at night; it recalls the stained glass windows of gothic cathedrals; ectoplasms of light that attract and at the same time disturb.

click here for "THE OBSCURE BODY OF COLOUR", edit by Manlio Brusatin - 2000 |

The sacrificial sense of a mystery rite – as critics have underlined – becomes even more pressing in the cycle “Gerusalemme, Gerusalemme” (“Jerusalem, Jerusalem”). Here the x-ray plates appear suspended in the “heavy” environment of a crypt: they become impressive thanks to the deformation of the figures in contrast with the hard stones of the sacellum. The Christological symbolism is clear. It is the pain that reflects from the rough walls, slips between the x-ray plates and impregnates almost everywhere through an almost cloying light. A cry seems to resound: “Jerusalem! Jerusalem!” [151], overshadowing the music composed by Meneghetti himself.

It is precisely the impending images from above; intersected by the sign of the Cross (“Golgota quotidiano” “Daily Golgatha” [152]), that makes the atmosphere unreal: everything tending towards a mystical ascesis. A breath of air is all that is needed; the breath of a viewer, to move the interaction of light and shadow that evokes the mystery. It is like “a fading of the body: being sublimed in the symbol of the Cross”. Nothing is inert: the traces of a pencil seem to have been born out of a subterranean force: these traces take on the profile of a lion enveloped in flames. The crosses are magnified, they take in all the space in which we move: they themselves become peopled with wanderers in search of Redemption. Meneghetti continues to forge his installations; among the most recent and significant works of his adventurous journey “beyond the columns of Hercules” of our imagination. Large metal boxes (“Light Boxes”, 1999] [153] containing substances and images of the spine illuminated from behind; “Paralleli vertebrati” “Vertebrate parallels” similar in size and form to trees, trunks of palms but of an unnatural colour. We are taken to a sort of disorienting mental landscape. The fantastic plates magnified beyond measure seem to reflect the disorders of our psyche, the most secluded knots entangled within our organism: so much so that we are forced to walk “through” these involucres of light: Reality and unreality blend: material and fantasy contaminated..

During the 1968 protest movement Meneghetti imagined humankind consumed by a social mechanism of which money was the “fuel”. Now, in an installation of 2000, he takes the Pietra del Vituperio (the stone of vituperation), which for centuries in Padua has housed those condemned to shame, as his point of departure; it appears scattered with thirty coins [154], round x-rays in plastic form [155] and distinguished by the tools of eating. These are “memories of betrayal”, repeated - as Meneghetti says – every time that “humankind loses itself to feed on money” (“Pietra del Vituperio, commestibile quotidiano” “The stone of vituperation, daily foodstuff”).

And now we reach the beginning of 2001, always using the installation, a series of computer elaborated photographs [156], showing sacks and corks roughly massed in great piles, “like masses of men without any possibility of vision or movement with anatomical shadows tossing and turning over them”. It is always existential symbolism that dominates; recalling works of thirty years ago or more, a sign of the extreme coherence in Meneghetti’s artistic development. Meneghetti is an endless furnace of creation.

Some of his sculptures have been seen more than once in Padua, such as the vertical chain of “heads” in ceramics (“Vertebrati paralleli” “Parallel Vertebrate”) [157-A] [157-B], or the base relief “Icaro” “Icarus” [158] in plaster, gold leaf and enamel, or the many layered wooden figures (“Maitresse mutante” “Mutant Maitresse”) [159], or those in “split” metal (“Omaggio a Giorgio” “Tribute to Giorgio” [160]).

At the same time we have the x-rays of the series “L’anima del quotidiano” “The day-to-day soul” [161]: they are impressions of everyday objects, such as televisions [162], telephones [163], shoes, computers, keys, pens, suitcases [164], bags , etc., similar to those objects we see in the x-ray security machines of airports (“Violazione della privacy” “Invasion of privacy”) [165]. Curiously: in our collective unconscious, these images, which should remain merely documentary, take on psychic implications, merging with the x-rays of human anatomy. Something strange is in the air, absorbing the ghosts that flow within us.

Then recapitulating recent facts and discussions – there is what Meneghetti calls “l’aura viandante” “The wayfarer’s aura”. It has been discussed at length, but it is worth while repeating the essential concepts, precisely because it is an issue that has effected the development of the very history of art in these last years. It is a form of “irradiation” that was born in 1979, when Meneghetti was struck by the x-rays he found himself looking at following an illness. In the exasperated fantasy of the artist those x-rays became significant: they were transformed, transmuted into artistic memory, that is to say into works of art. Many years have since passed. Meneghetti is now aware that he was then the unwitting initiator of a “proliferation” of x-rays seen from an aesthetic point of view. The examples collected in a dossier are numerous: they have been listed and studied in a special essay. The fact remains that Meneghetti has found himself as the leader of a trend: or at least a prototype.

156  157a

157a  157b

157b  158

158  159

159  160

160  161

161  162

162

163  164

164  165

165  166a

166a  166b

166b  166c

166c  166d

166d  166e

166e

X-Rays have been absorbed especially in the advertising field: but not only. That ghost-like luminescence, that negative appearance of bone structures, entering under the skin, into the flesh, the blood vessels, muscles; especially that sense of astonishing mystery, almost of taboo, on daring to enter inside the body of another human being, and perhaps finding oneself in a tunnel half way between life and death, indeed a stones throw from death… well, all this has come to be part of our current collective imagination.

An invention or a discovery: above all a priority that shows how Meneghetti’s art has become part of our social body: it is not a simple game of illusion, but a witness to a primary need of humankind, that surfaces always more. That is to say: Meneghetti’s “wayfarer’s aura” has left a permanent mark. It borns the cycle "ri-appropriazioni debite" (proper re-appropriations) [166-A] [166-B] [166-C] [166-D] [166-E]

click here for

"PASSAGES: MELTED-FLESH AND SOFTENED BONE", edit by Alberto Abruzzese - 2003

MENEGHETTI in the Third MILLENNIUM ![]() (available only in italian version)

(available only in italian version)